Worrying Fiscal Predicament Looms Large for the US

Dr Maurice Tse

18 September 2024

The US presidential election is now proceeding at full throttle. Long advocated by the Republican candidate, Donald Trump, measures including tax cuts, increased military spending, and economic stimulation are bound to pump up the government’s fiscal expenditures. His Democratic opponent, Kamala Harris, on the other hand, calls for expansion of social programmes, boosted infrastructural investments, and economic stimulus initiatives. While a tax hike is on the table, without a corresponding growth in revenue, federal debt will only stack up over time.

Over the past five years, the US government’s fiscal deficit has persistently remained above US$1 trillion while its debt level has been among the highest in the world. Surprisingly, neither of the two presidential candidates regards this as a priority. One cannot help but wonder if America’s economic future is at risk of a debt time bomb, potentially fulfilling the prophecy of the fall of the West.

When evaluating a country’s financial situation, it is necessary to understand that debt is the total sum of money owed at any particular time while a deficit occurs when the government’s spending surpasses its income, leading to larger national debt. Fiscal deficit and debt are usually compared against Gross Domestic Product (GDP) as the latter serves as a rough indicator of a country’s solvency.

Using a collection of data covering the period from 1946 to 2009, gathered from the International Monetary Fund, the World Bank, and the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development, American economists Carmen Reinhart and Kenneth Rogoff have conducted a study on 44 countries. Their work reveals a significant negative correlation between the government debt ratio and economic growth. In developed economies and emerging economies with a debt-to-GDP ratio over 90%, the median growth rate is lower by 1.5% and the average growth rate is lower by nearly 3% compared to economies with smaller debt obligations.

A government’s annual fiscal-deficit-to-GDP ratio consistently over 3% would cause alarm for many economists and international organizations. Take the European Union for example. Its Stability and Growth Pact, introduced in 1997, is designed to maintain sound public finances and facilitate economic growth by overseeing and controlling member states’ budget deficit levels and public debt levels. Under the pact, the annual budget deficit of each member is capped at 3% of its GDP and the public-debt-to-GDP ratio must be kept below 60%. Assessed against these criteria, the steadily high US fiscal deficits and public debts are inevitably a cause for concern among scholars and pundits regarding America’s economic future.

Under the catalytic effect of virtually zero interest rates and low debt costs over the past decade, escalating government debts have become a global issue. In June 2023, US President Joe Biden signed the Fiscal Responsibility Act passed by the Congress, which suspended the US$31.4 trillion debt ceiling until January 2025. At the beginning of 2024, the overall debt of the federal government stood at US$33 trillion, approximately US$28 trillion of which was held by the American public.

Figure 1 shows that the US public-debt-to-GDP ratio in 2023 almost reached 100% while the total debt-to-GDP ratio exceeded 120%, the highest level since the 103% recorded at the end of the Second World War. Thanks to strong economic growth and financial surplus, the total debt-to-GDP ratio fell to 23% in 1974. Upon Bill Clinton’s departure from the White House in 2001, that ratio registered at 32.8%. Since then, the US has seen fiscal deficits for 23 consecutive years.

As a matter of fact, the debt-to-GDP ratio approaching 100% is not necessarily a problem; rather, what causes concern is the continuous upward trend. The Congressional Budget Office (CBO) forecasts that the ratio will reach 116% by 2034 and even 163% by 2054. A persistent trend is sure to hamper the US economy in the long term.

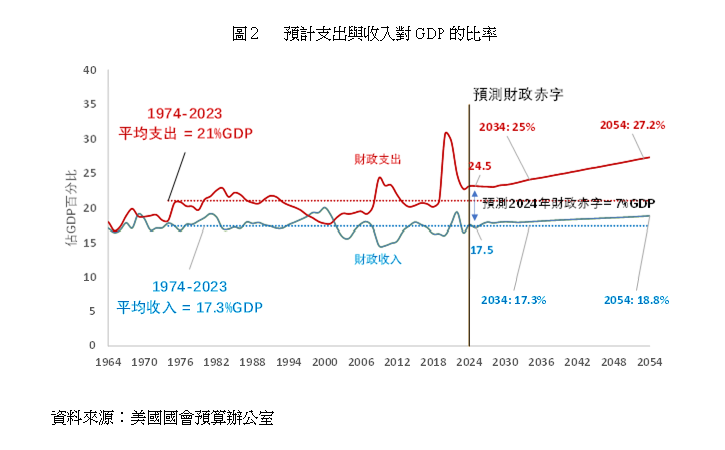

In June 2024, the CBO adjusted its forecast for the deficit for the same fiscal year, raising the amount by more than US$400 billion to US$2 trillion, which equated to 7% of GDP (see Figure 2). During the COVID-19 pandemic, the national deficit rocketed to an all-time high of US$3.13 trillion, representing 14.7% of GDP. By 2021, the deficit totalled US$2.78 trillion, or 11.8% of GDP.

CBO data indicates that US fiscal deficit has been accelerating: averaging US$138 billion in the 1990s, US$318 billion in the 2000s, US$829 billion in the 2010s, and even averaging US$2.23 trillion in the 2020s. During the past three years, massive deficits have arisen in an environment of economic growth, low unemployment, and stable national defence spending. The CBO therefore regards these deficits as structural and projects that the accumulated deficit between 2025 and 2034 will stand at the high level of US$22.1 trillion.

Recent deficits have stemmed from large outlays. Since 1974, with an average revenue share of 17.3% of GDP and an average expenditure share of about 21% of GDP, the annual average deficit-to-GDP ratio has remained between 3% and 4%. During the same period, revenue has stayed close to the long-term average level. The current expenditure-to-GDP ratio is around 24%. The CBO forecasts that it will remain high in the coming decade, approaching 25% in 2034 while the deficit-to-GDP ratio will reach 7.7%.

To settle the fiscal balance amounting to almost US$2 trillion, it is necessary to both raise taxes and cut spending. According to the US Internal Revenue Service’s latest data in 2021, the top 5% of income earners pay approximately two-thirds of income tax, the top 25% of income earners pay almost 90% of the total tax revenue, and half of the bottom income earners pay merely 2.3% of the total tax revenue. Evidently, any tax rise should be clearly targeted and should not dampen investment.

The Tax Cuts and Jobs Act of 2017 passed during Trump’s tenure as president has reduced both personal income tax rates and the corporate tax rate. A significant part of the Act is set to expire by the end of 2025. In the event of non-renewal, the CBO forecasts that accumulated fiscal deficit in the next decade will reach US$22.1 trillion. However, if renewed, the accumulated fiscal deficit is projected to surge by an additional US$4 trillion.

President Biden has promised not to raise taxes for families earning less than US$400,000 annually (95% of all families) but will raise taxes for the remaining 5% to accommodate the renewal of the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act of 2017. Nevertheless, experience in Europe shows that raising taxes on the rich to balance the budget, has, at best, uncertain effects.

At present, 80% of the US government’s fiscal expenditure is mandatory, with social security and healthcare being the two largest expenditure items while only 20% is discretionary, e.g. national defence and education. Apart from national defence, the actual discretionary outlay amounts to US$750 billion. With the proportion of people aged 65 or above now at 18% of the total population, annual spending on social security and healthcare has been accelerating unabated. Over the past two decades, these two items have not been subject to review by the Congress and both are in danger of running out of funding within 10 years. Needless to say, slashing expenses is easier said than done.

Excessive debt has driven up the interest costs for the federal government, which has now become the government’s third-largest expenditure item, with an average interest-cost-to-GDP ratio of over 3%. The CBO estimates that the interest cost will reach the US$1.7 trillion mark within a decade, impacting not only the operations of government agencies but also some social welfare programmes.

It is well known that US Treasury bonds, being the largest bond asset class, play a pivotal role in the global financial system. Given that the US Treasury has to refinance around one-third of the existing debt and fund the current deficit, bond auctions may not be effective. If anything goes wrong, market confidence could be undermined. Now that the credit ratings of US Treasury bonds have been downgraded by S&P Global Ratings and Fitch Ratings, foreign investors (who hold about 25% of US debt) may therefore exert pressure on the US to implement fiscal policy changes. For instance, urged by bond vigilantes during the mid-1990s, President Bill Clinton achieved four budget surpluses in his last term of office.

In its Annual Economic Report, the Bank for International Settlements also warns that rising debt exposes governments to the risk of a crisis similar to the UK government bond market turmoil in 2022. Investors at that time shied away from UK bonds, resulting in a surge in borrowing costs, currency depreciation, and chaos in the stock market.

All in all, the sustainability of a high fiscal deficit depends on economic growth rates, interest rates, overall debt levels, and currency stability. Against the backdrop of “the rise of the East and the fall of the West”, whether the US government is strong enough to support unlimited debt expansion is an enormous challenge for the next administration.

References

1. Annual Economic Report 2024, Bank of International Settlements

2. Budget and Economic Outlook, Congressional Budget Office 2024