Asymmetric Fertility Elasticities

- Countries around the world are struggling with below-replacement fertility rates, defined as 2.1 children per woman.

- Anecdotal evidence shows anti-fertility campaigns have seen great success, but most pro-fertility policies have had only a minimal effect.

- This paper presents systematic empirical evidence demonstrating fertility rates respond more to anti-fertility policies than pro-fertility policies.

- The asymmetry in the effectiveness of fertility policies can be explained by households’ loss aversion regarding living standards.

- The dynamic model with loss aversion implies fertility rates can fall on their own even without changes in the underlying economic fundamentals, providing a new angle from which to interpret the global fertility decline in recent decades.

- With asymmetric fertility elasticities, policymakers should set a higher fertility-rate target than previously thought and be extra cautious in preventing anti-fertility campaigns from overshooting.

Source Publication: Zhou A, Pang C, Engle S. Asymmetric Fertility Elasticities. Available at SSRN 4912608, 2024.

Many governments around the world are struggling with below-replacement fertility rates. Recent efforts to increase birth rates have produced disappointing outcomes, which contrast sharply with the success of anti-fertility policies implemented in the past. Is it systematically more difficult to raise fertility than to reduce it? If so, what are the micro foundations and the macro implications of this phenomenon? Zhou A, Pang C, Engle S. (2024) provides a comprehensive analysis of this issue.

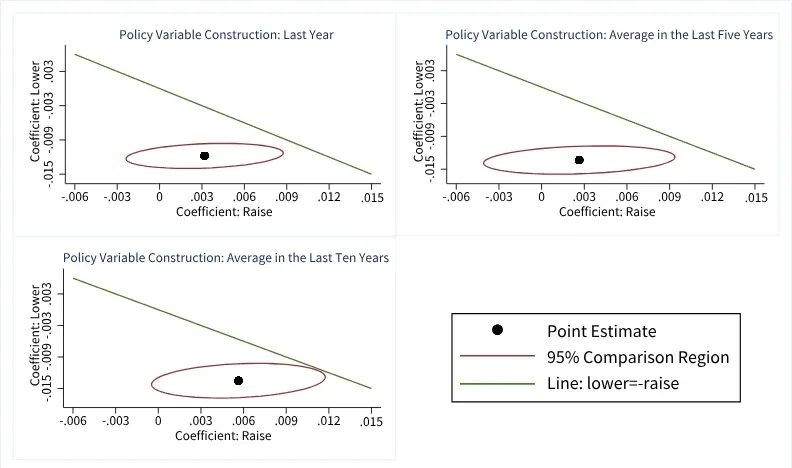

The study compares the impact of anti-fertility policies on fertility rates with that of pro-fertility policies in a range of econometric specifications. First, the study estimates fertility responses to policy stances using (1) panel regression and policy reversal specifications on aggregate-level data from the United Nations and (2) cohort-exposure design on individual-level data across countries from the World Value Survey (WVS). Furthermore, the study collects data on the funding of anti-fertility policies, estimates the elasticity of fertility in response to policy funding, and compares the results with the pro-fertility elasticities found in the literature.

The study then explains the empirical findings by developing a model that incorporates loss aversion from behavioral economics into a standard fertility choice model. Then, the study extends the model to a dynamic setting to explore the macroeconomic implications of asymmetric fertility elasticities.

Figure 1. The Asymmetric Effect between Anti-fertility Policies and Pro-fertility Policies

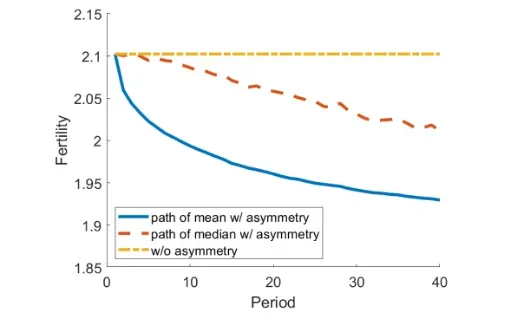

Figure 2. The “Slippery Slope” of Aggregate Fertility Rate

In both aggregate-level and individual-level specifications, the study finds anti-fertility policies are more effective than pro-fertility policies. Additionally, the study finds the asymmetric effects of fertility policies persist even after accounting for heterogeneity in policy intensities.

The asymmetry in the effect of fertility policies contradicts existing fertility choice models, which predict symmetric fertility responses to increases or decreases in the shadow price of children. To explain the empirical findings about asymmetric fertility elasticities, the study proposes a novel theory of fertility choice by incorporating loss aversion regarding living standards into standard models. Due to the trade-off between fertility and living standards in the budget constraint, households with loss aversion concerning their current lifestyle are more reluctant to increase fertility than to reduce it upon symmetric incremental changes in the shadow price of children.

The study then embeds the model with asymmetric fertility elasticities into a dynamic framework, where households’ reference point for consumption follows an adaptive updating process with random shocks. Asymmetric fertility elasticities have two important dynamic implications: (1) The fertility rate can decline on its own even without changes in the underlying economic fundamentals, and (2) if the government is concerned about fertility rates being too high or too low, the cost-minimizing fertility-rate target should be higher than previously thought.

A remarkable reversal has occurred in the past few decades as many countries have shifted their policy priorities from suppressing to maintaining or promoting childbirth. However, as this study shows, raising the fertility rate is significantly more difficult than reducing it.

The study offers a new angle from which to interpret the global fertility decline in the past few decades. Due to the presence of asymmetric fertility elasticities, random shocks are more likely to increase households’ lifestyle reference point than to decrease it. This increase in the lifestyle reference point then leads to the continuous decline in the fertility rate. Unlike traditional theories, this process doesn’t require exogenous changes in factors such as the return to education, the opportunity cost of children, and so on.

This study also has important policy implications for policymakers. Because loss aversion exerts downward pressure on fertility, fertility tends to decline on its own even without policy interventions. Therefore, governments have precautionary motives to set a fertility target higher than the replacement rate, which many policymakers previously thought was the optimal level (Striessnig and Lutz, 2013). Ignoring asymmetric fertility elasticities and targeting fertility rates to the replacement level can lead to significant welfare losses.

Striessnig, Erich and Wolfgang Lutz, “Can below-replacement fertility be desirable?” Empirica, 2013, 40, 409–425.