Racing Against Time: Using artificial intelligence to find and help people in emotional distress

Dr Michael Chau’s study uses the machine learning and rule-based classification components of artificial intelligence to find people online who are in emotional distress. Using these techniques may help health professionals locate struggling individuals faster, getting help to them before it’s too late.

This is game changing, as the timely identification of people in distress coupled with early intervention “can increase the awareness among parents, schools, educators, and public health providers and help prevent tragic incidents from happening … reducing the possible medical, financial, and social costs associated with suicide.”

A growing problem with no efficient solution

In trying times, both stress levels and screen time increase. The far-reaching effects of the on-going COVID-19 pandemic have pushed people’s entire work, school and social lives online – and also pushed some to the breaking point. Enter Dr Michael Chau, an Associate Professor at HKU Business School who specialises in artificial intelligence, text mining and data analytics.

Dr Chau’s May 2020 study published in MIS Quarterly is based on two premises: that emotional distress and suicidal ideation are constant problems for society; and that, while suicide rates in Hong Kong have remained relatively stable over time, there is an increasing trend of people, particularly youth, sharing their feelings of emotional distress, their suicidal thoughts and even their suicide notes on various Internet platforms.

This Internet content, including narratives and diary posts on various blogs and fora, as well as social media posts, provides an enormous data set. But while it is vital to find distressed people in order to have health and social work professionals help them, up until this point, locating them via their online posts has been a time-consuming and ineffective process which is usually conducted manually using standard search engines. Adding to this difficult situation is the fact that the agencies and NGOs tasked with finding distressed people are stretched thin, meaning that opportunities to help people in need are being missed.

Applying artificial intelligence to a public health problem

There is an emerging sub-discipline in the School’s Innovation and Information Management area: artificial intelligence. Traditionally used to explore customer opinions on products or gather public opinions on political candidates, in this study, Dr Chau takes a novel approach to sentiment analysis, using it to examine this urgent public health issue.

In his opinion, “Our research has important implications for social work practice. Emotional distress is a robust risk factor for suicidal behaviour and the early detection of high-risk individuals is the key to prevent future suicidal behaviour.” The positive effect this research could potentially have on society cannot be overstated – by putting an innovative spin on normally business-focused techniques, it is possible to address this persistent and pernicious problem in an entirely novel way, streamlining suicide prevention services and in the long run, saving many lives.

Designing a Chinese-specific system

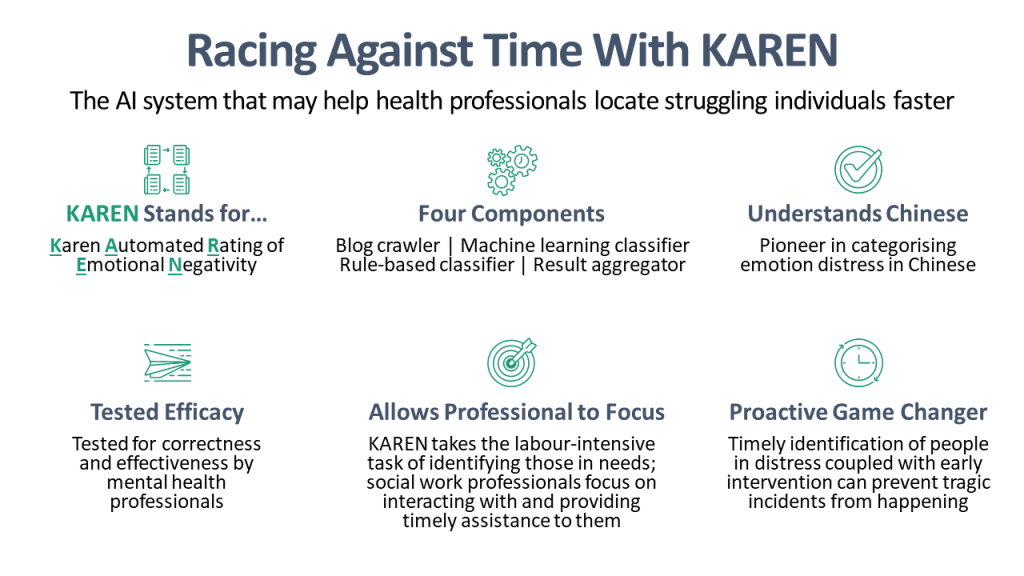

Dr Chau’s study centres designing a system called KAREN, which stands for “Karen Automated Rating of Emotional Negativity.” KAREN consists of four major components: a blog crawler, a machine learning classifier, a rule-based classifier, and a result aggregator. While the mechanics of each component are quite complex, their ultimate aim is simple: to sweep the Internet for keywords related to emotional distress, extract results, classify them and present them to the system user who can then decide whether or not action needs to be taken.

Breaking it down, the blog crawler sends out keywords entered by the user into the Internet, using search engines to find matches and then downloading the content of sites which contain the identified words. The two classifiers then take over, using a machine learning model and a rule-based model to classify whether a particular post shows emotional distress, based on given examples. Without getting too complicated, these models place words into different categories, like positive or negative emotions, risk factors and casual words.

While glossaries categorizing emotional distress exist in English, prior to this project, there were none in the Chinese language. So, in conjunction with clinical psychologists with experience in emotional distress and suicide, Dr Chau and his team developed a lexicon of Chinese words and phrases that could express emotional distress. The team also took into account other unique attributes of the language – such as the way people articulate fear, worry, sadness and anger in written Chinese.

During the classification process, the system assigns emotional distress scores to each sentence, based generally on the number of positive emotion versus negative emotion words found, with scores increasing if words in risk factor groups appear. These scores are then aggregated to provide a final score for the post or document – if the score is positive, then it is classified as showing emotional distress and flagged for follow up action.

To prove its effectiveness, KAREN was tested twice – first on a static data set to check if it correctly identified emotional distress, and then by users to see if mental health professionals could more effectively identify people in emotional distress online by using the system.

KAREN passed both tests with flying colours. In the data set test, KAREN performed better than other systems under most scenarios, correctly selecting and identifying worrisome posts. The professional evaluation test showed that professionals benefited from using KAREN, finding more posts showing emotional distress and performing their jobs more effectively than with another model.

Co-creation and collaboration benefit society

The proven efficacy of KAREN and the positive results from Dr Chau’s research will bring enormous benefits to Hong Kong society. Before the social unrest of 2019 and the pandemic of 2020, depression and suicide rates were already at high levels in the city. The added stress created by these two seismic societal events will not improve the situation for people in emotional distress or experiencing suicidal ideation – especially when the existing system for identifying people at risk is overstretched and under resourced.

Dr Chau shares that it is the mission of “NGO [staff and volunteers] to intervene when they see people showing emotional distress online, leaving a message through a contact method to try to establish a conversation with the individual concerned.” These cases “should be evaluated by NGOs and social work professionals, but they are not…because of a lack of resources.” It is precisely this gap which KAREN is aiming to close.

HKU Business School specialises in data analytics and practical applications for these analyses. By taking this primarily business-focused discipline in a new direction, Dr Chau has opened the door to new cooperative, co-creative ventures with health professionals and NGOs. In fact, he and his team collaborated with the Faculty of Social Science at HKU on this interdisciplinary research study, which won the INFORMS ISS Design Science Award 2020.

Next up for KAREN will be examining the system’s practicability and efficacy when processing data with a large number of “normal” posts and a small number of posts showing emotional distress to better represent real-world conditions; and analysing people through multiple posts to look at, and possibly predict, their emotional fluctuation. These future research directions will require input from professionals outside the Faculty: psychologists, sociologists, cultural anthropologists, and others.

In the system’s current form, when put to use, KAREN will take the labour-intensive task of browsing and searching for emotionally distressed people online away from social work professionals, instead allowing them to “focus their attention on interacting with and providing assistance to those in need,” according to Dr Chau. These efficiencies and time savings will be especially important in situations when people are in urgent need of help.

Proactively reaching out to save time and save lives

Ultimately, KAREN will pave the way for more proactive suicide prevention services. Currently in Hong Kong, traditional programmes offer suicide hotlines or web-based resources which are mostly reactive and passive, waiting for people in need to call for help. While it is vitally important for people who are in distress to seek help, they do not always do so.

If rolled out successfully, KAREN will allow these programmes to identify and proactively reach out to those in distress in a more effective way. This is game changing, as the timely identification of people in distress coupled with early intervention “can increase the awareness among parents, schools, educators, and public health providers and help prevent tragic incidents from happening … reducing the possible medical, financial, and social costs associated with suicide.”

It is Dr Chau’s great hope that this research will help people suffering from emotional distress get the care they need before it is too late. In fact, the system is named after his best friend who suffered from depression. Her name was Karen.

If you are having suicidal thoughts, or you know someone who is, help is available. Call 2896 0000 for The Samaritans or 2382 0000 for Suicide Prevention Services. HKU students may also contact CEDARS (the Centre of Development and Resources for Students) at https://www.cedars.hku.hk/cope/cps.

About the Research

References

Al-Naweb, L.W. (2021, February 1). ‘Covid: Suicide prevention help calls during lockdown’, BBC News. https://www.bbc.com/news/uk-wales-55751615

Barak, A. (2005). Emotional support and suicide prevention through the Internet: A field project report. Computers in Human Behavior, 23, 971-984.

Gilat, I. & Shahar, G. (2007). Emotional first aid for suicide crisis: Comparison between telephone hotline and Internet. Journal of Psychiatry Interpersonal & Biological Processes, 70(1), 12-18.

The Hong Kong Jockey Club Centre for Suicide Research and Prevention (2021). 1981-2018 Hong Kong Suicide Statistics. Hong Kong: The University of Hong Kong. https://csrp.hku.hk/statistics

Leske, S., Kõlves, K., Crompton D., Arensman, E., de Leo, D. (2020) Real-time suicide mortality data from police reports in Queensland, Australia, during the COVID-19 pandemic: an interrupted time-series analysis. The Lancet Psychiatry, 8(1), 58-63.

Luxton, D. D., June, J. D., & Kinn, J. T. (2011). Technology-based suicide prevention: Current applications and future directions. Telemedicine and e-Health, 17(1), 50-54.

Turecki, G. and Brent, D. A. (2016). Suicide and suicidal behavior. The Lancet 387(10024), 1227-1239.