The Violent Ripple Effects of Stock Market Losses

[This article discusses domestic violence. If you or someone you know is experiencing domestic violence, you are not to blame, what is happening is not your fault. There are numerous resources and refuges available to you. They are listed at the end of this article.]

Revealing a global problem

Domestic, or intimate partner violence (DV or IPV), is a horrible and pervasive part of life for much of the world’s population. Loosely defined as “any behaviour by a current or former intimate partner within the context of marriage, cohabitation or any other formal or informal union, that causes physical, sexual or psychological harm”, IPV affects mostly women and children and is perpetrated mostly by men. This menace is present in every corner of every society: a 2018 World Health Organisation Study found that 27% of women aged 15-49 across the world had experienced IPV at some point since the age of 15 – approximately 641 million women.

Domestic violence destroys lives, stunts careers and has enormous social and economic costs. While estimates vary, when “the victim’s pain and suffering, medical bills, lost productivity, judicial system expenses and lost productivity from the incarcerated offender” are taken into account, the estimated costs of DV in the US alone are USD460 billion per year; while socioeconomic costs in the UK are approximately GBP15 billion annually.

A study in The Lancet emphasises that “There is an urgent need to invest in effective multisectoral interventions, strengthen the public health response to intimate partner violence, and ensure it is addressed.” Many people are answering this call to action, and government agencies, non-government organisations, schools and other bodies across the world are involved in trying to stop DV.

Taking a finance-oriented perspective

One contributor is the University of Hong Kong’s Tse-Chun Lin, who recently co-authored a paper focusing on how negative emotional shocks can lead to domestic violence. Their work approaches this subject from a financial viewpoint, specifically how stock market losses “can affect stress levels within intimate relationships, escalate arguments, and trigger domestic violence.”

While their paper, appearing in the Review of Financial Studies, is written mostly in finance terminology, it is nonetheless extremely relevant to the dark, cruel world of domestic violence, which they define as “reported incidents of assault, aggravated assault, or intimidation by a spouse, partner, or boyfriend/girlfriend.” The paper begins with a discussion of “asymmetric utility” – the idea that the negative emotions that come with financial losses are not the same as the positive emotions associated with financial gains. This concept has long been used by finance researchers looking to explain unusual patterns in economics, such as the equity premium puzzle (which questions why US stocks have consistently performed better than US Treasury Bills for over 100 years); and the disposition effect (which is the tendency for investors to hold on to stocks that have dropped in value and sell stocks that have risen in value). But up until this paper, the concept had really only been studied experimentally. Instead, they take asymmetric utility out of the laboratory and into the private lives of people across America.

Their varied background research included a study that found “compelling evidence of domestic violence being triggered by emotional shocks related to losses in (American) football when the home team is expected to win”; and another which concluded that stock market movements affect people’s stress levels, an effect that was “reflected in a significant negative relationship between local stock market returns and hospital admissions for psychological conditions”. Yet another study determined that stock market-induced wealth shocks “strongly affect health outcomes, including physical health, mental health, and even survival rates.”

Finding a link between poor returns and domestic violence

Based on these and other findings, the authors developed a hypothesis: For individual people, negative stock returns affect stress levels within families and close relationships, in turn causing and escalating arguments and increasing domestic violence. A straightforward hypothesis, but one which required an elaborate model to properly test. They called this a “loss-of-control” model, based on a previous study in which the authors created an equation to measure the likelihood that a situation would escalate to violence through a loss of emotional control.

On the DV side of the equation, they built up a large sample of US domestic violence incidents from 2001-2016, using police reports from agencies covering tens of millions of people, and used this to calculate daily and weekly incident rates. On the stock market side, they constructed their own local stock market index for each US state which approximately mirrored individual investor returns at the state level, giving the model more granularity and making it more robust. They also note that while this model was not applicable to everyone, over 20% of American households hold direct stock investments and around 50% have either direct or indirect investments, meaning that “a sufficient share of the population is exposed to stock market movements to have a noticeable effect on their stress levels and consequent domestic violence incidents.”

They analysed their figures weekly, using stock returns calculated from Monday to Friday, as weekly measurements represent “larger and more meaningful wealth shocks”; and domestic violence incidents from the weekends only, since DV rates are consistently higher on weekends – starting from 4pm on Fridays (after the stock market closed) until Sunday at midnight.

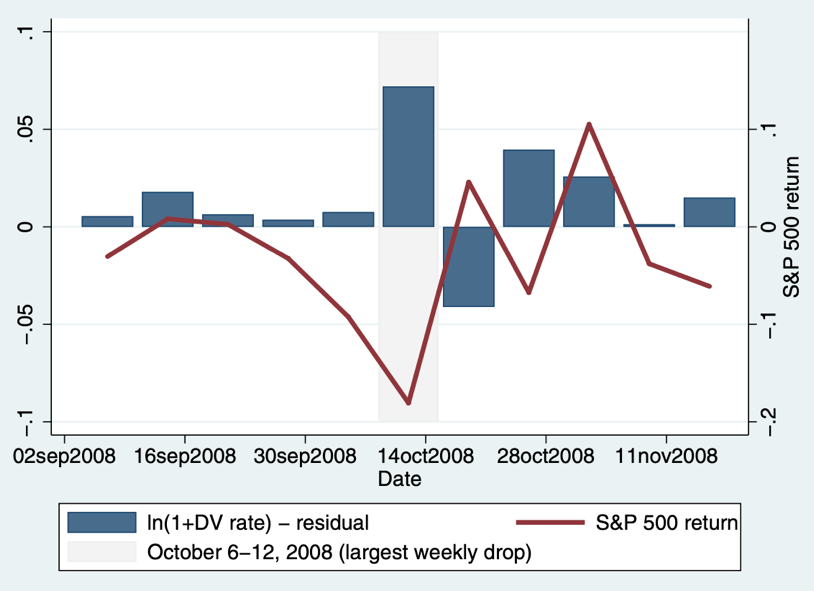

Before applying different types of analysis, adding controls and performing robustness checks, a clear, if simple, inverse relationship was immediately evident. The authors illustrated this with a graph of data from the weeks around October 2008, noting that, “During the week of [this] main stock market crash, domestic violence increases pronouncedly, while the following week experiences both strongly positive stock returns and significantly reduced levels of domestic violence.” Take a look:

Figure 1: October 2008 stock market crash and domestic violence

They then put in a great deal of hard work and statistical analysis, ultimately showing that this relationship holds firm when other variables are considered, such as seasonality, holidays, unemployment rate, and other variables. On top of this, the negative relationship only lasts for the week in question and varies from week to week. All strong signs that their hypothesis is solid and valid.

The authors also tested whether any type of emotional shock could lead to DV – positive or negative. After analysis they found only losses, not gains, were related to violence. Plus, the higher the losses, the greater the rates of violent incidents. This relationship was also strongest in areas with the highest percentage of people participating in the stock market; was not driven by local economic factors such as plant closures or mass layoffs; and was specific to domestic violence and not other crimes that “might conceivably be correlated with stock returns like assaults, murders, sex offenses, robberies, and drug offenses.”

Revealing a potential path out of the darkness

Prof. Lin and his co-author’s findings are both stark and disturbing, given the strength of the relationship. A 13% decrease in weekly stock returns correlates to about a 2.7% increase in domestic violence. This mirrors the findings of other studies – the “American football” study that found a 10% increase in IPV when the home team lost unexpectedly, for example – but it is the first real-world evidence of a link between stock market returns and DV.

Their paper contributes to the study of asymmetric utility and helps to advance knowledge on the subject of finance. It also makes important advances in the social sphere, in that it shows how negative stock returns which create wealth shocks that affect shareholders’ social relationships and “generate emotional cues that may lead to arguments escalating and manifesting in domestic violence”.

Most importantly, their findings may help other people and organisations find ways to address one of the many root causes of household violence – in the US and around the world. Investing in stocks is inherently a risky business; to paraphrase many pre-investment warnings, “the price of stocks may go down as well as up”. Their conclusion cautions that “stock investments may entail risks that are broader than the effect of financial losses”. Indeed. If losing a significant amount of money causes stockholders to spiral out of control and leads to a spike in DV, they surmise that “standard economic models measuring utility only by wealth may underestimate the total ‘risk’ of stock investments.”

Extrapolating from this conclusion, by digging further into household investment decisions, future researchers may uncover ways to lessen the emotional shocks of investments gone wrong, or perhaps steer people who are more susceptible to strong feelings away from more volatile investments altogether.

Domestic violence is a complex, costly and all-around horrible problem that must be addressed. Studies like this, that reveal small but significant drivers of the wider issue, are vitally important to decreasing domestic violence incidents and protecting the most vulnerable.

Here are some links to domestic violence information and resources in different parts of the world.

China

China domestic violence helpline app:

- [https://www.reuters.com/world/china/thousands-call-new-chinese-domestic-violence-helpline-app-2022-09-01/]

Hong Kong

The Hong Kong Federation of Women’s Centres Women’s Helpline: 2386-6255

- [CHI: https://www.womencentre.org.hk/Zh/Services/counselling/womenhelpline/]

- [EN: https://www.womencentre.org.hk/En/Services/counselling/womenhelpline/]

Information on types of domestic violence and contact details for several refuge centres, from the Hong Kong government’s Social Welfare Department:

- [CHI: https://familyclic.hk/zh/topics/daily-lives-legal-issues/domestic-violence-and-assistance/assistance/]

- [EN: https://familyclic.hk/en/topics/daily-lives-legal-issues/domestic-violence-and-assistance/assistance/]

Australia

Australia domestic violence support resources: https://au.reachout.com/articles/domestic-violence-support

Canada

Canada family violence resources and services: https://www.canada.ca/en/public-health/services/health-promotion/stop-family-violence/services.html

UK

The UK government’s “Domestic abuse: how to get help” page:

https://www.gov.uk/guidance/domestic-abuse-how-to-get-help

The US

The US National Domestic Violence Hotline: 1-800-799-7233

About this Research

Tse-Chun Lin and Vesa Pursiainen (2023). The Disutility of Stock Market Losses: Evidence From Domestic Violence. The Review of Financial Studies 36(4):1703–1736.

References

Card, D., and G. B. Dahl. 2011. Family violence and football: The effect of unexpected emotional cues on violent behavior. Quarterly Journal of Economics 126:103–43.

Domestic violence and assistance. 2014 – 2021 Community Legal Information Centre, The University of Hong Kong. Retrieved 10 May, 2023 from https://familyclic.hk/en/category/topics/daily-lives-legal-issues/domestic-violence-and-assistance/

Engelberg, J., and C. A. Parsons. 2016. Worrying about the stock market: Evidence from hospital admissions. Journal of Finance 71:1227–50.

Lomborg, B., Williams, M. A. February 22, 2018. The cost of domestic violence is astonishing. Retrieved May 12, 2023 from https://www.washingtonpost.com/opinions/the-cost-of-domestic-violence-is-astonishing/2018/02/22/f8c9a88a-0cf5-11e8-8b0d-891602206fb7_story.html

P v. C [2006] HKFAMC 27; FCMC 9655/2005 (26 September 2006). https://www.hklii.hk/eng/hk/cases/hkfamc/2006/27.html

Sardinha, L., Maheu-Giroux, M., Stöckl, H., Meyer, S.R., García-Moreno, C. 2022. Global, regional, and national prevalence estimates of physical or sexual, or both, intimate partner violence against women in 2018. The Lancet 399, issue 10327:803-813.

Schwandt, H. 2018. Wealth shocks and health outcomes: Evidence from stock market fluctuations. American Economic Journal: Applied Economics 10:349–77.

United Nations Academic Impact. Examining Domestic Violence Around the World: The Cost of Doing Nothing. Retrieved 11 May, 2023 from https://www.un.org/en/academic-impact/examining-domestic-violence-around-world-cost-doing-nothing

Violence against women prevalence estimates, 2018: global, regional and national prevalence estimates for intimate partner violence against women and global and regional prevalence estimates for non-partner sexual violence against women. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2021. Licence: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO.

Walby, S. (2009). The cost of domestic violence: Up-date 2009. Lancaster: Lancaster University.