Future Anxiety – How COVID-19 Led People to Save More Money

Photo credit: iStock.com/bob_bosewell

In times of uncertainty or crisis, most people are inclined to stop, take stock of the situation and take whatever action (or inaction) is necessary to avoid further trouble. The financial manifestation of this reflex is “when in doubt, save”. Or, in the words of Aesop, the legendary Greek story writer, “It is thrifty to prepare today for the wants of tomorrow”.

Few events have created as much uncertainty in our lifetimes as the COVID-19 pandemic, a disease that has upended lives and lifestyles around the world for two years and counting. As we – hopefully – approach the end of the pandemic, scholars and researchers are beginning to examine its wide-ranging effects and uncovering some interesting and helpful information about how and why things happened as they did.

Take the recent study by Chen Lin and Mingzhu Tai from the HKU Business School, conducted with collaborators from the University of California, Berkeley and the Chinese University of Hong Kong. Their paper addressed a fundamental worry for almost everyone during the pandemic: Money. Specifically, they examined how people in the U.S. saved money in response to COVID-19.

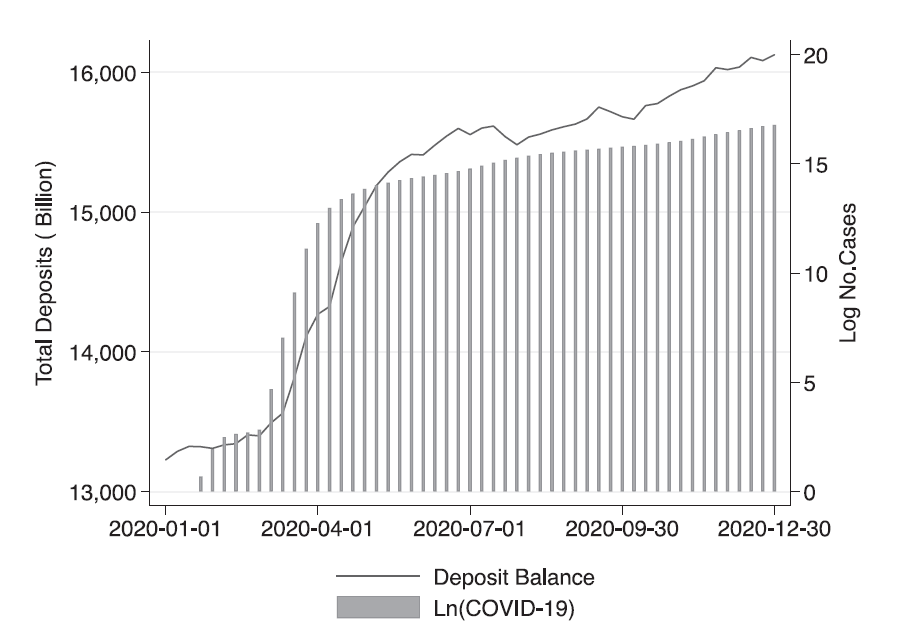

Noting that U.S. banks had deposits increase from $13 trillion in January 2020 to $16 trillion by the end of the year, their study, inquisitively titled, “How Did Depositors Respond to COVID-19?”, sought to uncover the drivers behind these enormous deposit inflows.

The aggregate trends of deposit in U.S. banks during the first year of the COVID-19 pandemic. Source: Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis

Painting a picture of how a rapidly-spreading deadly disease affects people’s bank accounts money is extremely difficult. Nevertheless, the authors were keen to try.

Investigating several promising points of view

Drawing on vast resources of data, the authors looked into five existing perspectives on what may have caused the surge in deposits.

- The “precautionary savings” view – a.k.a. Aesop’s credo – whereby households saved more, including through bank deposits, due to employment and income security concerns triggered by the pandemic. The testable predictions associated with this view propose that local [COVID-19] infection rates will have had (a) a positive relationship with local concerns about future job losses and incomes, (b) a positive association with increases in local bank deposits, and (c) a negative relationship with the local deposit interest rates.

- The “flight-to-safety” view stresses that individuals reallocated part of their savings into bank deposits and other safer investments to avoid the financial disruptions triggered by the pandemic. It predicts that infection rates would have had a negative effect on local deposit interest rates among safer banks and a positive impact on insured deposits.

- The “drawdown-and-deposit” view notes that firms, having made large withdrawals from their lines of credit, would have then deposited this money into banks. This view proposes a positive relationship between county-level infection rates and increased local bank deposits, especially by firms; a negative relationship between infection rates and deposit rates; a weak relationship between infection rates and deposit rates; and no connection between infection rates and deposit rates when firms did not draw down their credit lines.

- The “demand for deposits” view proposes that the banks themselves may have attracted funds by raising deposit rates and cutting new lending – a notion which implies that local infection rates will be positively related to local deposit rates.

- The “policy response to the pandemic” view suggests that the U.S. government’s economic policies enacted in response to the pandemic – the Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security Act and the Paycheck Protection Program – were responsible for the increased deposits, since more federal funding was given to counties with higher COVID-19 infection rates. Thus, the view goes, the more local infections, the higher the local deposits.

Each of these views produced a great deal of information through which the researchers had to sift to find their answers.

Analysis and synthesis

The authors analysed three types of data along their journey of discovery: (1) weekly branch-level data on deposit interest rates (drawn from over 10,000 bank branches across the country) and county-level data on COVID-19 cases; (2) information on the quantity and composition of deposits (to see if differences in COVID-19 infections are associated with changes in local bank deposits); and (3) measures of individuals’ anxieties about jobs and future income losses (to see whether these concerns altered spending behaviour).

Within these data sets, the researchers had to set down rigorous parameters to control for a myriad of variables, among them – bank branch-specific factors, national financial market fluctuations, state-level economic conditions and demographics, and time-varying national and state macroeconomic policies. They also set rules on what banks would be chosen for the study (those that were seen by investors as “too big to fail”), and what data from firms would be considered when testing the “drawdown-and-deposit” view (the degree to which local firms change their cash holdings, revolving credit and total debt).

As usual, some of the trickiest data to measure were the less tangible human-centric variables – anxiety about jobs and future income. To gain these measurements, they tapped into three primary data sources: Using Google Trends, they measured the intensity with which people searched online for information about job losses and savings; they employed individual surveys, asking whether the participants expected someone in their household to lose a job, and whether they had reduced their spending due to concerns about future income losses; and they examined weekly data on per capita employment figures and unemployment insurance claims at the county level.

Which perspective best explained the phenomenon?

The analysis strongly supported the precautionary savings view, as local COVID-19 infection rates were positively associated with an intensification of anxieties about future job losses, increased expectations of future income losses and a concurrent reduction in spending due to these expectations. Infection rates were also positively associated with a boom in local bank deposits, especially retail deposits, and declines in the interest rates offered on local deposits – each of the testable questions received a solid “yes”.

On the other hand, the flight-to-safety view was not supported, as the study did not find that local infection rates were associated with a larger reduction in local deposit interest rates or a larger increase in insured deposits. Nor was the drawdown-and-deposit view confirmed – no weaker connections between county-level exposure to COVID-19 and deposit rates were found, nor were there any larger increases in wholesale business deposits relative to retail banking deposits.

The demand-for-deposits view findings were inconsistent, as COVID-19 infection rates were associated with material declines in deposit rates, rather than increases. This negative relationship between deposit interest rates and infection rates also indicated that neither national- nor state-level macroeconomic policy had any causative effect, leaving the policy response perspective also unsupported.

As it turns out, human factors turned out to be the key to answering the question: Anxiety really does galvanise people into action.

“Why was 2020 different?”

While this study focuses on COVID-19’s effects on deposits, it echoes and augments research on how banks generally provide liquidity during periods of economic hardship. The authors note that in the 2008-2009 global financial crisis, deposits did not suddenly surge, meaning that banks were less able to provide liquidity; while during the pandemic, the enormous increase in deposits meant that they could.

And so, they asked, “Why was 2020 different?” The authors believed that a key difference between the two crises is that the 2009 financial crisis “was at its core a financial crisis that triggered intense concerns about financial stability, while the COVID-19 crisis was at its core a public health emergency that triggered intense anxieties about future income.” A striking point.

They also highlighted that by 2020, a decade on from the crisis, the U.S. public had experience of federal government’s “aggressive, far-ranging, and largely indiscriminate support of banks” and ordinary people making savings decisions were perhaps less concerned about the stability of banks, the distinctions between types of deposits or differences in financial performance between banks. These factors may have helped make it easier for individuals to decide to put their savings into banks in 2020.

Of the five equally plausible and well-thought-out views, only one held up under analysis: The precautionary savings view, or Aesop’s adage. There are many potential conclusions to be drawn from this, among them perhaps that large-scale government policies often do not have the effect that is intended; that the effects that businesses have on the banking system are dwarfed by those of individual consumers; and that banks themselves may not hold much sway over the general public. Future research may or may not examine these ideas.

But what seems to be certain is that people, when faced with large-scale crisis and uncertainty, will become cautious and conservative and seek to create their own stability and security. In an apt coda to this study, an article published in late 2021 in the New York Times quoted a paper by four economists which commented that “although large by historical standards, the savings accumulated by U.S. households during the pandemic do not appear to be ‘excessive’ when set against the extraordinary need of many American families.”

The article went on to say that “Millions of Americans could be buffeted by financial volatility again with little safeguard as new variants of the virus emerge. For some, that reality has already begun.” Shortly afterwards, the Omicron wave of infections hit the United States and then Hong Kong.

About this Research

Levine, R., Lin, C., Tai, M., & Xie, W. (2021). How did depositors respond to COVID-19?. The Review of Financial Studies, 34(11), 5438-5473.

References

Acharya, V. V., and S. Steffen. 2020a. ‘Stress tests’ for banks as liquidity insurers in a time of COVID. VoxEU.org.

Britannica, The Editors of Encyclopaedia. “Aesop”. Encyclopedia Britannica, 26 Mar. 2020, https://www.britannica.com/biography/Aesop. Accessed 25 March 2022.

Browning, M., and A. Lusardi. 1996. Household saving: micro theories and micro facts. Journal of Economic Literature 34:1797–855.

Carroll, C. D., and A. A. Samwick. 1998. How important Is precautionary saving? Review of Economics and Statistics 80:410–9.

D’Acunto, F., T. Rauter, C. Scheuch, and M. Weber. 2020. Perceived precautionary savings motives: Evidence from digital banking. Working Paper, Boston College.

Li, L., P. E. Strahan, and S. Zhang. 2020. Banks as lenders of first resort: Evidence from the COVID-19 crisis. Review of Corporate Finance Studies 9:472–500.

Reinhart, C. M., 2020. This time truly is different. Project Syndicate, March 23. https://www.project-syndicate.org/commentary/covid19-crisis-has-no-economic-precedent-by-carmen-reinhart-2020-03.

Smith, Talmon Joseph (December 7, 2021). ‘Americans’ Pandemic-Era ‘Excess Savings’ Are Dwindling for Many’. New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2021/12/07/business/pandemic-savings.html