Beyond the Butterfly Effect: How an ancient civil exam shaped the China of today

Past events can obviously have a profound effect on the future; but can these effects be measured and quantified? Two professors at the HKU Business School, Professor James Kung and Dr Chicheng Ma, and Dr Ting Chen of Hong Kong Baptist University, recently attempted to find out. They co-authored a paper on the impacts of China’s long-lived civil examination, the keju, on the modern-day society and economy of the country. They discovered that success in this ancient examination in particular locations led to a measurable effect on modern economic development in the same locations in the present day.

Yesterday affects today – but how?

The premise of the “butterfly effect,” originally a concept in meteorology, is that a single flap of a butterfly’s wings can set off a chain of atmospheric ripple effects that might eventually create a tornado. When applied to the human experience, it means that one small event or chance encounter in the distant past has the power to change the course of history.

While this idea has been wildly dramatized in popular culture – exploring the fatal consequences of dinosaur hunting or the paradoxes of time travel for example – the premise is still fascinating, and leads to recurring questions like “How much does the past influence the future?” and “Can we measure the extent of this influence?” Professor James Kung and Dr Chicheng Ma of the HKU Business School, and Dr Ting Chen of Hong Kong Baptist University, all experts in Chinese economic history, explored these questions by examining the link between a historical institution, the culture it generated and modern economic development.

The endurance of the keju

The earliest meritocratic institution in the world, the keju was an imperial examination system which began in the Sui dynasty, around 587 AD. The exam was then substantially expanded and consolidated during the Song dynasty, in approximately 960 AD, and became fully institutionalised during the Ming dynasty in 1384 after a brief interruption by the Mongols, and lasted until its demise in 1905. The keju was a mechanism for examining and then selecting officials across the country. Split into three levels, prefectural, provincial and imperial, the exam was held every three years, testing candidates’ writing skills and knowledge of Confucian thought and literature.

The exam was distinct in three ways. First, it was open to all males regardless of their social background, meaning that “a ‘commoner’ – someone whose ancestors had never passed even the lowest level of the exam – was eligible to sit for the civil exam so long as he passed each level…in the established sequence.” Second, it was comparatively corruption-free, with examiners being unaware of candidates’ identities and facing harsh punishment if they favoured a particular candidate over another, with some even being put to death!

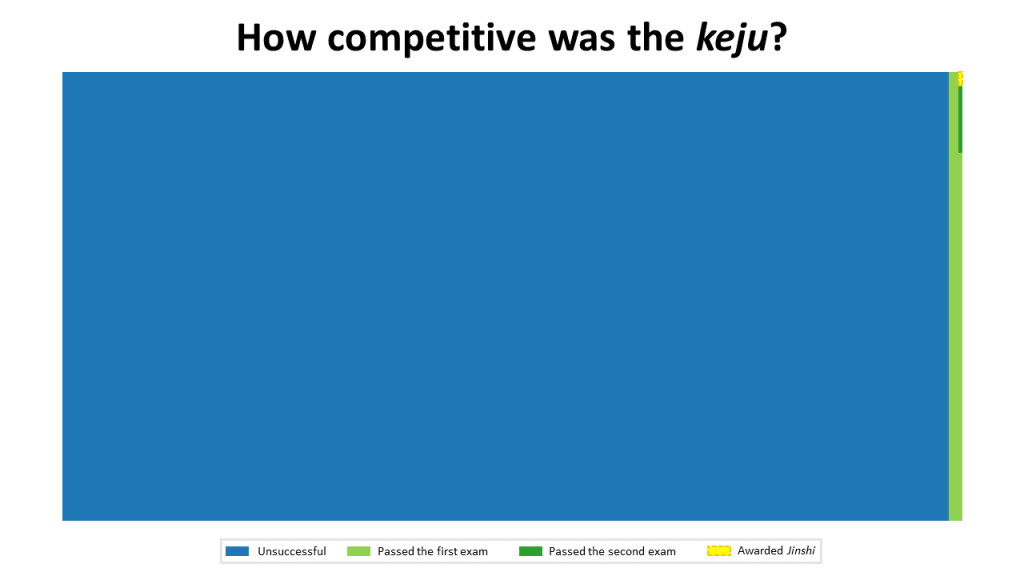

Lastly, the keju was highly competitive. To proceed to the final imperial level of the exam, the jinshi, candidates needed to get through the first two levels. Becoming someone that passed the jinshi (such a person was called a jinshi) was exceptionally rare: the pass rate for the first exam was around 1-1.5%, the second 6% and the final level 17.7% – an overall pass rate of about 0.016%.

For those who did pass, the rewards were incredible. They were held in the highest regard, guaranteed positions in mid-to-high level government administration with salaries on average 16 times a commoner’s wages. They often also invested in various businesses – further enhancing their income and bringing fame and fortune to their families. The corollary was of course that the exam system also “produced a large number of men who experienced the bitterness of repeated failure and spent gloomy lives in hopeless despondency, lamenting their misfortune.”

Most people saw the jinshi as “the ultimate qualification to achieve.” Indeed, the desire to succeed in the civil exam was so strong that young children “were made to recite no fewer than 2,000 characters from an ancient Confucian textbook for children after just one year of study.” As the researchers show, the exam had a formative effect on the structure of Chinese society for centuries.

A time travel experiment

This enthralling history led Professor Kung and his teammates to examine the long-term effect of the keju on human capital outcomes. Their hypothesis evolved from observing what looked like a strong positive relationship between the number of jinshi in prefectures during the Ming and Qing dynasties and the current economic success of those prefectures.

Their goal was to determine if this relationship was causal and if so, how this effect endures in the modern day. Easier said than done! To obtain their results, they needed to navigate a sea of variables while avoiding dangerous bias-related obstacles lurking beneath the surface.

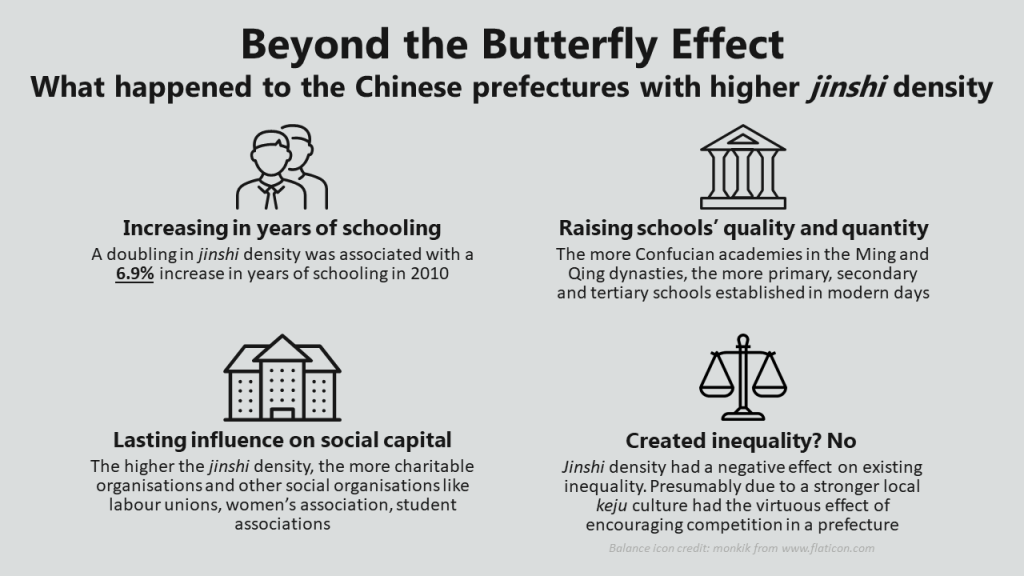

They began by calculating the density of jinshi across 278 Chinese prefectures, normalised by population. This revealed that for every 10,000 people, a doubling in jinshi density was associated with a 6.9% increase in years of schooling in 2010 – years of schooling being one measure of current economic prosperity. An interesting start. Given the many forces that could affect jinshi density, they then devised an instrumental variable to add rigour to the experiment: a prefecture’s shortest distance by river to the nearest pine and bamboo forests.

How is this significant? Because pine and bamboo were two vital ingredients in ink and paper production back in the day – which were in turn necessary for producing textbooks and reference books used to study for the keju. Without ink and paper – no books and thus no keju study materials. Further analysis using this variable confirmed that the initial result – higher jinshi density leading to more years of schooling in the modern day – was likely a causal one.

Case closed! This was not the work of some random butterfly, but a clear and measurable link from the distant past to the present day, correct?

Not quite.

Exploring the effects of the cause

The team needed to test exactly how the keju had produced this effect, so they came up with the hypothesis that it “had bred a culture of valuing education which was…transmitted across generations.” For this, they accessed the 2010 Chinese Family Panel Survey, a “nationally representative, biennial longitudinal general social survey project [that] documents changes in Chinese society, economy, population, education and health.” After controlling for various factors, and linking the surveyed respondents to their ancestors via surname and hometown characteristics, they found that ancestral jinshi density had a strong correlation with the respondents’ perception of the importance of education – the respondents wanted their children to receive more education, and spend more time helping their children with their homework; while the children themselves performed better in school and spent more time studying.

In addition to cultural transmission, the researchers believed that there were other ways that jinshi density could influence present-day education. They looked at the quality and quantity of schools – and sure enough, there was a positive effect on the number of Confucian academies in the Ming and Qing dynasties, on the number of primary and secondary schools established in the early 20th century and on the number of universities established throughout the 20th century.

Then they considered social capital, and again, jinshi density in a particular prefecture positively affected first the strength of clans in that area (as measured through the number of clan genealogies), and later, the number of charitable organisations and other social organisations like labour unions, women’s association, student associations and so on – essentially, more jinshis meant greater social capital in a prefecture. The same was true of political capital – more jinshis meant more high-ranking officials, up until communism took hold in 1949, and “the political elites were no longer confined to those coming from a literati background.”

The researchers also suspected a negative impact: that jinshi density could contribute to socioeconomic inequality by widening the gap between those who have no access to education and those that did – i.e. that resources would be poured into families likely to take the keju exam and not given to other families. In this case, their suspicions were incorrect – jinshi density had a negative effect on existing inequality, “presumably because a stronger local keju culture had the virtuous effect of encouraging competition in a prefecture,” which in turn created more inclusivity. An accidental effect perhaps, but a welcome one.

Putting it all together: patterns of cultural persistence

So, what does this intriguing look into the past tell us? One takeaway is that “some things are built to last” – and certainly the keju falls into this category. That this ancient institution and the culture It generated still sends cultural echoes through Chinese society is nothing short of remarkable – its effects are still measurable in education, educational infrastructure, social and political capital and in a comparative lack of inequality. As Dame Carol Propper, President of the Royal Economic Society, commends the authors in her letter acknowledging them for having won the 2020 Society Prize: “Your paper makes an important contribution to the understanding of why education, rather than material wealth, is considered important as a transfer to the next generation in some cultures, but not in others.”

Another observation, for researchers in particular, is “choose your variables wisely.” Professor Kung and his teammates deserve praise for their razor-sharp insights on how to examine the past. Using “river distance from the nearest pine and bamboo forests” as a way to measure the availability of study materials; and “satellite observed night-time lights in 2010” as a stand-in for a prefecture’s economic prosperity are excellent examples of lateral thinking producing good results. Again, to evoke the commendation of Professor Propper: “Your paper is a great example of how newly collected data can speak to big picture issues in economics in a simple, yet powerful way.”

But the final, and perhaps most important, piece of learning is that while a butterfly’s wings may eventually produce a tornado, it is the actions of people and the institutions they build – or tear down – that have the most profound effects on our world. Perhaps the solutions to some of today’s most pressing problems lie under the thin soil of the past, waiting, like gems, to be uncovered through the careful analysis of historical data.

About the Research

Sources:

Bradbury, R. (1952). A Sound of Thunder, in R is for Rocket. New York: Doubleday.

Ho, P. (1962). The Ladder of Success in Imperial China, New York: Columbia University Press pp. 114–16.

Institute of Social Science Survey, Peking University (2015). China Family Panel Studies (CFPS), https://doi.org/10.18170/DVN/45LCSO, Peking University Open Research Data Platform, V39

Ji, Y. (2006). ‘Mingqing kejuzhi de shehui zhenghe gongneng: yi shehui liudong wei shijiao (The function of Keju on social integration in the Ming-Qing period from the perspective of social mobility)’, Shehui (Society), vol. 26(6), pp. 190–214.

Keju (Imperial Examination System), Feb. 2008, en.chinaculture.org/library/2008-02/16/content_22184.htm.

Lorenz, E.N. (1993). The Essence of Chaos, U. Washington Press, Seattle (1993), page 134

Miyazaki I. (1976). China’s Examination Hell, Yale University Press, p.121

Shang, Y. (2004). Qingdai Keju Kaoshi Shulu Ji Youguan Zhuzuo (Review of the Civil Exam in Qing China), Tianjin: Bai Hua Wen Yi Chu Ban She.