- Firms spend significant resources on lobbying government agencies—80% of the 500 largest U.S. firms lobbying Congress also engage in lobbying executive agencies.

- Firms lobby executive agencies for two main reasons: to exchange relevant information with government agencies and to secure favors from them (i.e., the information channel and the influence channel, respectively).

- The information channel is supported by an increase in lobbying of agencies that start to issue more rules relevant to the firm’s business.

- The influence channel is supported by intensified lobbying of agencies that launch investigations into firms’ activities, grant special regulatory exemptions to these firms, and provide them with government contracts.

- Firms target their lobbying efforts toward agencies that offer the greatest benefits, and agency employees reciprocate by granting favors in exchange for potential future career opportunities. This quid pro quo dynamic is reflected in the observed results being more pronounced in agencies with stronger “revolving door” ties to the private sector.

- The 2024 Chevron decision weakened agency power, thereby decreasing the value of lobbying; consequently, firms that lobbied executive agencies experienced more negative stock reactions to the decision.

Source Publication:

Michelle Lowry and Ekaterina Volkova, “Corporate Lobbying of Bureaucrats,” SSRN Working Paper, November 2024.

Executive agencies play a pivotal role in shaping the regulatory environment by crafting rules, enforcing regulations, and overseeing government contracts—all of which can have a profound impact on businesses. For firms, this potential impact creates a clear incentive for firms to influence these agencies, particularly during the critical stages of rulemaking and enforcement. In this context, lobbying emerges as a key tool that companies use to mold the regulatory landscape to their advantage.

Unlike politicians, whose decisions are often swayed by electoral cycles and campaign contributions, agency officials are not elected, serve longer terms, and are less susceptible to direct political pressures. As a result, engaging in lobbying efforts with executive agencies is both more complicated and strategically crucial for firms operating within heavily regulated industries. However, the dynamics of such lobbying remain underexplored in the literature.

Lowry and Volkova (2024) examine the mechanisms underlying lobbying efforts targeting executive agencies, addressing questions of how, why, and how much firms influence bureaucratic decision-making. The study also explores the broader economic implications of such lobbying, the motivations of agency officials, and the factors that determine its effectiveness.

The authors analyze lobbying data from the 500 largest publicly listed U.S. firms in the CRSP-Compustat universe for each year between 1999 and 2023. Drawing from a wealth of data sources, including the Senate’s Office of Public Records, the Federal Register, Freedom of Information Act Requests, and USASpending.gov, they track lobbying expenditures, regulatory actions, investigations, and enforcement activities.

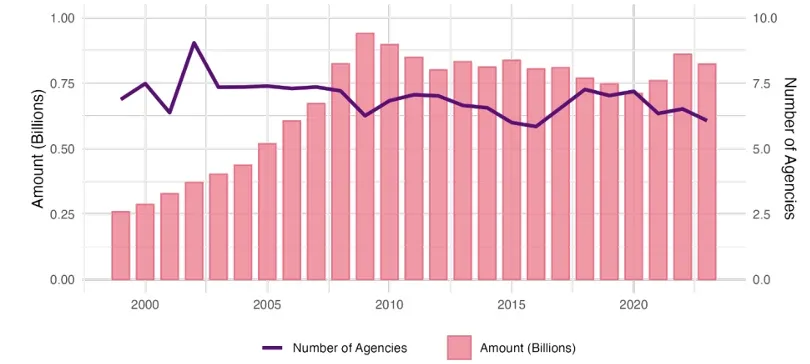

As shown in Figure 1, firms, on average, lobby around six different agencies annually, and this trend has remained relatively stable over time. Lobbying expenditures saw a sharp increase between 2000 and 2009, reaching nearly $1 billion, but have since stabilized or slightly decreased.

Figure 1 Aggregate Lobbying Dollars and Average Number of Agencies Lobbied (Per Company)

Note: This figure shows the total lobbying dollars spent by companies, on average each year, as depicted by the pink bars and labeled on the right-hand y-axis. It also shows the average number of agencies lobbied, as depicted by the purple line and labeled on the left-hand y-axis.

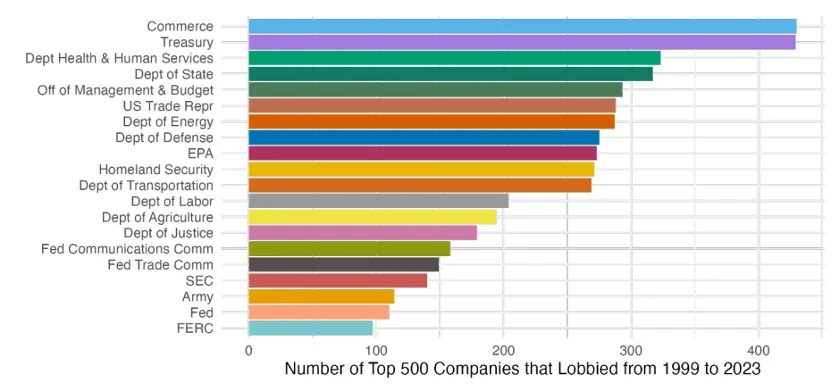

Figure 2 Distribution of Agencies Most Frequently Lobbied

Note: The bars represent the total number of companies that lobbied each agency during the sample years.

Firms typically engage in lobbying for two primary reasons: to exchange information with agencies and to influence regulatory outcomes.

The first motivation, known as the information channel, centers around firms offering their expertise to agencies that may lack industry-specific knowledge. Many regulatory agencies are tasked with overseeing complex industries but don’t always have the technical know-how required to craft effective regulations. By lobbying, firms provide valuable input that helps shape more informed, relevant policies. The study confirms firms are especially proactive in lobbying when agencies are engaged in rulemaking that directly affects their business interests, underscoring the importance of the information channel.

The second motivation, the influence channel, occurs when firms seek to directly obtain specific benefits from the agencies. These benefits can include receiving exemptions from rules, pushing for more favorable wording of final rules, or getting better outcomes in enforcement actions. The study highlights compelling evidence of the influence channel, particularly during periods of significant regulatory change. For instance, firms facing investigations are more likely to engage in lobbying efforts when substantial penalties are at stake, and those that do often experience more lenient enforcement outcomes. Firms that lobby during rulemaking periods tend to see positive abnormal returns—higher stock returns relative to the S&P 500—suggesting the market recognizes the potential regulatory advantages stemming from such lobbying efforts.

As mentioned above, lobbying executive agencies differs from lobbying Congress in that agency officials are less influenced by political pressures. Instead, their motivations are more shaped by career considerations, particularly the opportunity to transition between public- and private-sector roles. This “revolving door” creates a unique dynamic in which firms seek to build relationships with agency officials, who may eventually move on to lucrative private-sector positions.

The study highlights that agencies with higher levels of revolving door personnel turnover are more susceptible to lobbying activity. This finding reflects the strategic value firms place on fostering connections with individuals who may hold the key to favorable regulatory outcomes. This dynamic is particularly pronounced when lobbying is driven by the influence channel and when firms are seeking contracts from agencies.

In 2024, the U.S. Supreme Court overturned its ruling in Chevron v. Natural Resources Defense Council, significantly altering the regulatory landscape by limiting the discretion of executive agencies in interpreting laws in court. This decision raises important questions about the continued efficacy of lobbying efforts aimed at agencies whose regulatory authority has been diminished.

The study highlights a significant market response to this unexpected shift: firms that had lobbied executive agencies in the previous year saw a marked decline in abnormal returns following the Chevron ruling. This finding suggests that, as executive agencies’ regulatory authority was reduced, the strategic value of lobbying partially diminished.

This study underscores the significance of lobbying executive agencies—a channel through which firms extract private benefits that had previously been underexplored. It emphasizes the necessity of scrutinizing this activity to ensure both firms and agencies are held accountable for their actions. These issues contribute to public distrust and raise critical questions about government accountability.

To address these issues, reforms aimed at curbing the revolving door and enhancing transparency could reshape corporate lobbying practices, fostering a more equitable and accountable regulatory environment. Such reforms could improve the integrity of lobbying efforts, mitigate public concerns, and restore trust in the regulatory process.